My words on RJ Barrett and Jarrett Culver were all about finding dissimilarities and assessing future prospects based on said dissimilarities. With Zion Williamson and Brandon Clarke, there’s no doubt who sits where in the pro prospect hierarchy: Zion is on top and will forever be the shining diamond in this rough draft class of 2019. But that doesn’t mean these two gladiatorial young men don’t descend from a similar line of 0.1 percenters; the elite athletes in a sport dominated by elite athletes. I will never forget what Lamar Odom once said of JaVale McGee; after praising his athleticism, Odom implied McGee needed to improve as a player, “because the game is called basketball, not run and jump.”

I have no idea what Zion’s or Clarke’s verticals are. I don’t know how fast they run a 40 or a three-quarter court sprint. I’m clueless as to how many reps they can pound out at 185. These are two wildly athletic players, probably more so than Mr. Run & Jump, JaVale McGee, but, to Odom’s critique, Williamson and Clarke are basketball players from their fingertips down to their toes. They are players with high basketball IQs, selfless ethos, and developing jump shots. But the easiest and most obvious of their virtues remain of the visually physical variety. For this exercise, we will examine their physicals, efforts, and skills.

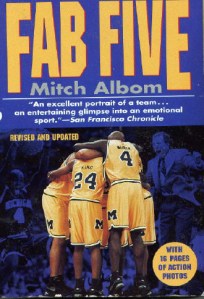

LAHAINA, HI – NOVEMBER 21: Zion Williamson #1 of the Duke Blue Devils takes a shot over Brandon Clarke #15 of the Gonzaga Bulldogs during the finals of the Maui Invitational college basketball game at the Lahaina Civic Center on November 21, 2018 in Lahaina Hawaii. (Photo by Mitchell Layton/Getty Images)

Williamson is a 6-7, 280-some-pound behemoth, a jackhammer with a predator’s reflexes. All (most?) sports have a way of visually conveying the unique strengths of their participants and basketball probably more so than most. There’s Zion with shorts and a tank top, a pair of shoes and socks. His massive arms are uncovered, on display for all; his broad chest stretching the letters across his jersey to unexpected breadths. There’s no hiding his physical imposition. His speed, power, and elevation are obvious to untrained eyes. He plays as if he’s shot out of a cannon, hits a target, sprints back to the cannon, reloads himself, and booms all over again, covered in sweat and the fear of opponents.

Brandon Clarke isn’t the slobber-inducing eye candy of Zion. He’s 6-8, around 215-pounds. If you saw him at the airport, he’d just be a run of the mill tall college basketball player in a jumpsuit with a backpack, but when the record drops and the ref says go, Clarke employs the dexterity of a crab, able to move side-to-side as fluidly as forward and backwards. He skinnies up that lean frame and slides through screens like a basketballing Mister Fantastic, he can deftly switch onto any opponent – big, small, medium, black, white, green, it’s all the same (which isn’t to say he’s flawless defensively, but we’ll get into that). And the jumps? Clarke’s legs appear to be powered by some kind of hydraulic system that’s been surgically installed into his body without any visible traces of its insertion. How else to explain his hyper pursuit of opponent shot attempts or the screaming missile dunkers he hurls through the rim? He dunks with the clean ripplelessness of Lob City DeAndre Jordan or the world’s sleekest cliff diver; he blocks shots like that Russian condor, Andrei Kirilenko. It’s possible that within his hydraulic enhancement, Clarke’s ability to anticipate and react to basketball events was upgraded; a software improvement of sorts. The more likely explanation is that Clarke has committed himself to achieving optimal physical condition for playing basketball and has refined his technique through hard work and dedication.

Trying hard matters, but as the Wizard of Westwood, Mr. John Wooden told us, we also don’t want to mistake activity for achievement. Williamson and Clarke are exemplars of a valuable athleticism and effort combination and both are, for the most part, proficient in their distribution of effort. Steals and blocks are not the best indicators of defensive impact, but they are one of the few available measures to track defensive activity. Clarke, who plays in the low-profile West Coast Conference (WCC), registers over 3 blocks and 1 steal per-game with a block rate over 11%. And comparing Clarke’s blocks and steals in 20 games vs non-Power Conference teams to 8 games against Power Conference teams, we see nearly identical numbers: vs non-power: 3.1 blocks and 1.1 steals, vs power: 3.1 blocks and 1.5 steals. Zion is tallying over 2 steals and nearly 2 blocks each game, making him one of just two players in the country (UW’s dynamic defensive wing, Matisse Thybulle being the other).

Effort doesn’t begin or end with trackable defensive stats. If you watch Duke play, it doesn’t take long to notice that Williamson exists in a state of perpetual sweat. His great wide chest and rib cage expands and collapses as lungs pull in and push out huge amounts of air. It could just be that he’s a naturally sweaty guy, but then you see him sprinting, shuffling, hurling that mass of body into opponents, the rim, the floor – any target, reached at high speed with buckets of sweat flying soaking the court. He doesn’t stop. Following the Gonzaga game in November, Williamson apparently had “full body cramps” (per ESPN telecast on 11/27) and required three IVs. The cramping and IVs can be in part attributed to effort and part to conditioning which needs to be acknowledged and will be below. That’s also not to say that his effort is risk-free. You don’t have to watch too many of Duke’s defensive sets to see his eyes lusting after the ball; hungry, ready, prepared to take it and fly away with violence and bad intentions – and then he catches himself and re-tracks his man.

Clarke’s motor doesn’t run into the red with the frequency or intensity of Zion’s, but at this point, the 22-year-old (nearly 4 years older than his Duke counterpart) is likely a smarter, more judicious player. It’s not that Clarke conserves his energy like I do or like present-day LeBron James, rather his movement is more efficient, his burst-heavy gambling and risk-taking occurring much more infrequently. But see Clarke defending on or off the ball, see him knifing through screens without ever losing his man, see him double and recover, eating up space like Pac-Man in a Gonzaga jersey, see him tracking missed shots on the glass and you see effort of focus. His awareness and ability to be mentally present in all situations means he doesn’t miss boxouts or switches, he isn’t caught ball watching and rarely ball chasing. He puts out maximum effort: getting his butt low in perimeter defensive events, moving his feet to gain post position on both sides of the ball, elevating for rebounds without exerting unnecessary energy due to being out of position. Awareness is no doubt a skill but combining it with effort optimizes for efficiency.

Perfection shouldn’t be expected from these prospects, or any player for that matter. If perfection is the pursuit, playing with circles is a more appropriate endeavor. And when we look at skills, both Zion and Clarke have real and clear deficiencies counterbalanced by athleticism, effort, and basketball intellect, but they are not perfect.

Regardless of how you feel about the growing prominence of the three-point shot in modern basketball, it’s a skill critical to floor and lineup balancing. To-date, Williamson has attempted 48 3s and is hitting 29%. The form and release on his shot are consistent, but he doesn’t do a great job squaring up and his release is out instead of up. The Stepien’s Cole Zwicker covered both his mechanics (~10:20 mark) and potential defensive schemes a limited jumper result in at the next level (~4:05 mark) in this excellent and thorough video breakdown. Players who see the type of defensive treatment that Zion will likely see include Ben Simmons, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Draymond Green. Each of those players, like Zion, has a high basketball IQ and are above average passers. Giannis and Simmons utilize cutting and athleticism as additional counters to sag off treatments. Given Zion’s superhuman-type explosiveness, passing, and IQ, it’s easy to envision ways around these treatments, though the most effective counter will be developing into at least an average three-point shooter.

In the clip below which includes some poor Virginia defense, Zion is able to use a player helping off of him twice on the same possession: the first to build up a head of steam and better track an offensive rebound (made much easier by his defender’s poor positioning and awareness) and the second to fill a gaping hole with a well-timed cut and emphatic dunk shot.

His height and length (listed 6-10 wingspan) have the potential to create pesky challenges. In multiple games this season, whether on post catches or dribble drives, longer, taller players have been able to either block or disrupt his interior shot attempts. Syracuse’s 7-2 Paschal Chukwu and Texas Tech’s 6-10 Tariq Owens immediately come to mind as rangy athletes who were capable of harassing his interior looks. For any success those teams had, Williamson countered by drawing fouls and shooting 10 (Texas Tech) and 14 (Syracuse) free throw attempts. His motor and quickness are such that he can get to the loose ball before opponents are even registering there is a loose ball.

If opponent length could cause him minor hassles, his own weight could cause more serious issues. I’m nowhere near qualified to write about the amount of strain Zion’s force puts on his joints and ligaments, but given his speed and elevation, the impact coming down has to be hellacious. Since I saw him in high school, I’ve always had this foreboding sense that injury awaits and it’s likely more of a superstitious feeling than anything rooted in sports science. There’s just something about his generational athleticism, to say nothing of his game, that screams: Too good to be true. I’m fearful of losing it, particularly because I wonder if measures could be taken to reduce its likelihood of occurring. At 280 or 285 or whatever, Zion isn’t in bad shape by any means, but is in optimal basketball shape? For an 82-game grind with a devil-may-care approach akin to young Dwyane Wade or Gerald Wallace, optimal condition is a must. Is optimal 265? 267? At what point does the loss of mass reduce effectiveness? For basketball in 2019, these are the questions that can differentiate long, successful careers from merely good or, I shiver, injury-ravaged ones.

If distance shooting and his physical makeup are potential caution flags, the rest of his game is a joy to behold. For a player who won’t turn 19 until July, Zion’s body control and footwork are exquisite. His size coupled with his hangtime allows him to elevate, absorb or avoid contact, and finish with regularity. He frequently employs a hard spin move off the dribble and executes it without slowing down, his feet and brain in working in perfect synchronization. His handle is good; he keeps it low and has some wiggle, but the right hand (he’s lefty dominant) still needs a bit of work. It’s effective against college big men, but given how he’ll be schemed against in the NBA, it will be interesting, particularly if his jumper doesn’t develop, to see how useful it is or becomes. Off the dribble he has a pull-up jumper that looks a little better than his three-ball, but still lacks in fluidity. Finally, his passing and court awareness are an icing on the cake of sorts. He’s not a passer or creator like LeBron James, but when you have players who are so physically overwhelming, you don’t always expect to see advanced court vision and awareness as the players are often accustomed to imposing their will with force. Not only is Zion a capable passer, but going back to high school, he’s been a willing creator whose passes zip through space with velocity and accuracy. Playing alongside better shooting with better court spacing, it’s easy to see this skill being more fully realized.

A final side thought on what Zion faces at the pro level: despite him attempting over 9 free throws-per-40 minutes, I’ve noted numerous plays where he draws obvious fouls that aren’t called. And as the pro comparisons march through the internets, my first thought on seeing him officiated differently from his peers is LeBron and Shaq. The strength advantage those two MVPs have always had over their peers created officiating challenges and it’s not hard to imagine the beefy, booming Zion running into the same inconsistencies with NBA refs.

I didn’t see any of Brandon Clarke in his 2-year stint at San Jose State, but I’ve seen a ton of his single season at Gonzaga and he struck me early on as a player who plays far bigger than his 6-8, 215-pound frame. In terms of eye testing, Clarke leaps off the screen, out of the picture, and soars across the Spokane skyline. He’s most fun and most effective on the defensive side of the ball which I’ve covered in more depth above. But in an NBA where designated positions matter less than skills, Clarke will have ample suitors.

So is he a three, a four, a five? A combo forward? A 4-5? Is he conditionally all of the above? Alongside a pair of bigs who can shoot from the perimeter, there’s no reason Clarke can’t defend modern NBA big wings. In a small-ball lineup, he could easily slide to the 5. The weaknesses I’ve seen in his defense are against stronger, heavier players. Particularly, UW’s Noah Dickerson, a throwback, deep position-seeking post player who weighs at least 235 pounds and Tennessee’s Grant Williams who’s built more like Julius Peppers than Julius Hodge. Both were able to pin Clarke and limit his length and explosiveness. This isn’t to say Clarke isn’t strong, rather that body type, lower center of gravity and thick base, create positional problems for him. Fortunately for Clarke, the NBA doesn’t go to the post with the frequency of earlier eras, nor has it fully optimized the market inefficiency of the PJ Tucker type, but these matchups in addition to mountains like Jokic and Embiid are going to give Clarke trouble in a man-defense setting. His other defensive vulnerability, despite great lateral quickness and effort, is guarding smaller, quicker guards. Clarke is athletic enough to recover when getting beaten, but not going overboard on closeouts and better utilization of his length as a cushion against quickness will improve on what is already an elite defensive profile.

Offensively, Clarke is a much simpler player. He’s attempted just 12 threes with the Zags (made 4) and is a 68% shooter from the line. I don’t believe Clarke’s pro value to be contingent on shooting ability and I have questions about his touch around the rim, but Cole Zwicker makes a strong case for Clarke’s shot development and touch; which happens to be a single skill that could determine Clarke’s destiny in this great global game. He’s most noticeable in and around the paint for a Zags team that’s not short on skilled scorers, but in that painted area, none are more efficient than Clarke who’s currently shooting nearly 70% on 2s. It’s not just that he’s mean as a dunker, but Clarke has already developed as a roll man, regularly catching lobs from point guard Noah Perkins and dunking them down like bolts of lightning from Zeus. He has an off-the-dribble game, but it’s not something I’d expect to see at the next level unless it drastically develops. From my viewing, he’s been better in catch-and-shoot situations as his mechanics hold up there. Similarly to his off-the-dribble game, I don’t anticipate Clarke being used much as a hub or scoring option in the post though with Gonzaga, he gets good position down low with a strong, low base. If he does get the catch inside, it’s almost a guarantee he’s attacking left shoulder with either a little righty jump hook or a mini dribble drive.

The above isn’t the type of clip I’d normally seek out, but it’s a perfect example of Clarke’s footwork and timing in the pick-and-roll while also capturing his non-stop movement. On a single possession, he goes through two screen-and-roll motions, posts up his man, and executes a hand-off. It doesn’t matter that nothing came of it on this possession; rather, the unceasing pressure creates breakdowns that result in easy buckets.

Clarke gets his shots with the Zags (nearly 10 FGAs/gm), but his value is that he doesn’t need them to be effective. He doesn’t need entire sets drawn up or committed to him in order to produce. Between P&R, offensive rebounding, competent grab-and-go- skills, and running the floor (Clarke runs the floor like a man possessed; against St. Mary’s I saw him get a layup just by sprinting the floor off a make), he can be an efficient fourth or fifth scorer. Developing as a shooter is the kind of swing skill that pushes him from highly competent role player into starter on a competitive playoff team.

There could be better athletes or better dunkers in college basketball than Zion Williamson and Brandon Clarke. But there isn’t anyone who better combines athleticism with ability than these two genetic lottery winners (h/t Bill Walton). These brothers in arms pull you in with their highlight dunkathons and keep you there with commitment and effort. If the game was called “run and jump,” they’d still be top-tier. Instead, the game is basketball and timing, nuance, effort, awareness all matter as much as vertical jumps, agility drills, and points-per-game. There exists a substance beneath the style of this fashionable game, and Clarke and Williamson, for whatever stroke of luck and hard work, embody both: the luck to be blessed with world class athleticism and the willingness to work hard to untap it and release it into this ethereal existence.