Two of the league’s youngest, shiniest, brightest and most volatile stars are residing in the same Sunshine State and we all get the luxury of watching these mountains of agility, power and skill square off four times this season. I’m not talking about Dwight Howard (not that bright), Pau Gasol (not that young), Andrew Bogut (not that volatile) or DeAndre Jordan (just not enough). Blake Griffin and DeMarcus Cousins are captivating for what they’ve done in two short years and maybe even more for what they haven’t done; which is reach their stratospheric potentials.

Last night, Monday night, these two giants competed; not against each other, but for my attention. Big Cuz did his thing in Sacramento and went bananas during a third quarter stretch where he seemed to galvanize himself, his team and fans. His emotion rises in pitches and can be tracked by events: A blocked shot on the defensive end leads to Cousins making a face, a scowl that takes place while the 22-year-old barrels down the court, sprinting to get to the offensive end where his excitement almost results in turnovers, but instead it’s a hustle play, a jumper that extends the Kings’ lead and it’s followed by more sprinting and obvious satisfaction. There are sequences like this throughout the game: Cousins makes a layup, gets a steal on the other end and never missing a play, he gets a dunk going back the other way. He’s uplifted, raised to the rafters by a combination of his own energy (barely harnessed) and the sounds of the crowd urging him on, lifting him higher.

Down I-5 in Los Angeles, I focused of my attention on the Cavs-Clips game, Chris Paul vs. Kyrie Irving; which somehow turned into the Dion Waiters show. Point guard and ball handling clinics aside, I kept an eye on Blake Griffin; one of the league’s most recent poster boys. His face is more recognizable than Arian Foster’s, maybe better known than Mitt Romney among the 25-and-under set. And tonight he’s just OK. He catches lobs from CP3 that have a similar impact on the crowd as Cousins’ antics. The big difference is where Cousins wears his heart on his sleeve, unable to contain even the faintest emotion; wearing the worst poker face in the NBA, Blake is cool, expectant, nonchalant. In a deadpan tone, “I ferociously dunked on that man’s face, put him on a poster, got seven million views on YouTube, so what? It’s what I do.” And the crowd reveres him for it—it’s LA, it’s Hollywood, it’s cold, emotionless, unfeeling, sunglasses at midnight—swaggalicious! But it’s not enough tonight, the 20 points, the dunks, the improved post game, the passes, the increased defensive activity; it’s not enough and he ends the game with the poorest plus/minus of any Clippers player. The stat’s not all-indicative or all-encompassing, but it does tell us that the Clips were outscored when Blake was on the court tonight. The above isn’t to say that Griffin is emotionless. Rather, his furies are selective; taken out on rims and refs. A man can’t dunk with the aggression of Griffin without having something built up, pent up, bottled up…waiting to explode.

Griffin’s an embraceable face, a marketable style, a chiseled athlete that Subway and Kia throw wads of cash at in attempts to lure him into promoting their products. He’s rugged and competitive; he’s the perfect athlete to place on a pedestal. But DeMarcus? Last season he demanded a trade and (in a roundabout way) got his coach fired. To casual fans, he’s known as much for his outbursts and tantrums as he is for his dominant play and potential. To the unknowing, he’s the enfant terrible. How much of is this fueled by anger compared to immature indiscretion is impossible to know, but it’s fair to assume both parts sources drive Cousins’ madness.

And of course these two young innocents have exchanged words and occasional elbows on the court. After a physical game last season, Cousins called Griffin an “actor” and said the NBA “babies” him. Griffin responded with some jokes and questioned Cousins’ reputation. It was a nice tit for tat that can link players together through the media while driving them apart as people and potential teammates (all-star games, Olympics).

Despite Griffin developing somewhat of a reputation as being one of the league’s golden children (especially from a marketing and advertising perspective), he’s simultaneously becoming known for his flopping and posturing. He’s prone to the extended stare after a big play, the glare after a hard foul; he can be seen as a tough guy who doesn’t back it up. If you’re a Clippers or Griffin fan, you see him getting under the skin of his opponents, helping his team win while maintaining his cool. His cool is part of his being, part of his on-court persona and skill set. Given his effort and physicality, it’s hard to make a case that his cool results in any on-court detachment. This is where the primary break with DeMarcus occurs. Where Griffin’s immaturity and petulance are merely annoying for fans and opponents, Demarcus’s antics and eruptions are distracting for him and his teammates. He’s battling the refs, battling opponents, battling coaches and worst of all, fighting himself.

At risk of delving into a wormhole of sociological speculation, I’ll only briefly touch on the drastic life differences these two young men endured growing up. Griffin was raised in a two-parent home in Oklahoma; one where he was homeschooled until eighth grade and played for his father in high school. Alternately, Cousins grew up in a single-family household, attended multiple high schools in Alabama and steadfastly refused to take any responsibility for his behavior. A fully fleshed-out essay could easily be built around the differences in their childhoods and the challenges they face today as a result, but other than this brief review, I’d rather stick to the men we’re dealing with today, not yesterday.

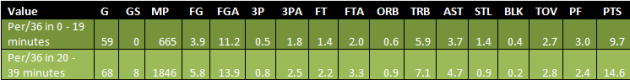

Literally speaking of yesterday, I watched Griffin and questioned whether or not he’d actually developed over his first couple seasons. While Cousins’ statistical arrow is pointed straight up, Griffin’s stats have been slightly, but steadily, dipping down. Looking at it from a purely statistical standpoint or even watching the games, you can see Griffin’s impact isn’t what it was when he was a rookie. Meanwhile, Cousins has become the heart, soul, tears and pulse of this Kings team. Instead of looking at this as Griffin already reaching his ceiling, it’s not as simple as that. Both players are filling a void on their respective teams. In Los Angeles, Chris Paul has revised the climate from the Blake Show to a CP3-led, guard-initiated attack. It begins and ends with Paul; an on-the-court general; one of the league’s most intense competitors who’s willing do whatever (ask Julius Hodge) it takes to win. The team (Blake included) has followed his lead. Griffin’s learned to play off of his PG, drifting towards the basket on CP’s defense-collapsing drives, hitting the offensive boards on CP misses or kick out misses, he takes advantage of slower fours by hitting what’s become an improved mid-range jumper. In Sacramento, as Tyreke Evans has either plateaued or regressed, Cousins has taken on the role of catalyst. When Paul Westphal was fired last season, it was evident there was a Westphal-Cousins conflict and new coach Keith Smart was wise to tap into the mercurial big man’s psyche and give him the confidence and latitude to succeed—which he clearly did last year: 4th overall in rebounds/game, only center to finish in the top-20 in steals/game, 3rd in TRB%, led all centers in usage rate. Cousins arrived with heavy footsteps and swinging limbs, announcing his arrival to anyone in earshot or sight.

None of this is to say one player is better than the other, but rather each player’s giving his team exactly what they need. CP3 might be the Clips’ version of Jean-Luc Picard, but Blake is the swag, the electricity, the vitality. And Cousins fulfills both of those roles in Sacramento…because that’s what he has to be for them to have any chance of success. These kids leave everything on the court every time they play. They play, they care, they’re upsettable, excitable, irritable, irrationally talented. And for all their differences (vertical vs. horizontal, NoCal vs. SoCal, one-parent vs. two-parent, stability vs. volatility), they have just as much in common, although both would probably puke if they had to admit it.

Tale of the Tape