It’s a bit of Captain Obviousness at his most obvious, but after this latest weekend of norm-crushing outputs, it’s still worth acknowledging the statistical rampages on which Russell Westbrook and James Harden are presently embarking.

Harden’s latest salvo was fired across the electorally-commentating Gregg Popovich’s snout to the tune of 25-points, 11-rebounds, and 13-assists which marked back-to-back triple doubles and the third consecutive game of at least 24-points and 13-assists. The last guy to go three straight 24-13s was the Canadian maestro Steve Nash.

Russ responded in kind with an even nervier performance on Sunday (the day of my birth and the day after his own birth so thanks for the bday entertainment) when he unloaded for 41-points, 12-rebounds, and 16-assists while turning the ball over just twice and shooting 67% from the field. That OKC lost to the ever-struggling Magic is just details in the micro, but worrisome in the macro where there’s a collective evidence that disallows celebrating the individual performance in basketball unless there’s a corresponding team success. Aside from the tiresome debates of our day about winning, stats, and the individual in modern basketball, you can be reassured that Russell’s performance was of a most rarefied air. Since 1983-84 which is as far back as Basketball-Reference’s game logs go, only one other player has posted the 40-10-15 triple double and that was three-time NBA champion and ghost chasing coverboy, LeBron James – though Bron needed a full 47 minutes while Russ needed a mere 38. (As an aside, the night Bron executed the 40-10-15, the Cavs lost to Denver in a classic Carmelo-Bron duel where Anthony put up 40 in a game his Nuggets won in overtime. Can we get this on some NBA OnDemand platform? Please? Or is that too much to ask given that we can’t even get a workable version of League Pass?)

We’re a mere 10% into this new season, but inching further away from the small sample size theater and into some world of sustainability. These gaudy stats (32-9-10 with 5 turnovers and a 41% usage for Russ, 30-8-13 with 6 turnovers and 34% usage for Harden) would seem to taper off at some point and yet that assumption is driven by two notions: 1) neither player is physically capable of keeping up these torrid paces, 2) a single player carrying a disproportionate load eventually becomes an impediment to team success.

Physically speaking, Russ has proven his Wolverine-type resiliency over the years as he hadn’t missed a single game through the first five seasons of his career until Patrick Beverley notoriously dove into his leg during the playoffs. This is a man who had his skull dented and continued to play. He appears capable of carrying anything and has the second-highest usage rating in league history at 38.4% in 14-15 which he achieved over 67 games in a season when Kevin Durant was frequently absent with foot injuries.

Harden is a case in stylistic contrast, but has proven himself to be a player with a single-minded emphasis on forward progress. He’s in the midst of a stretch of over 300 games dating back to 2013 where he’s averaging right at 10 free throw attempts-per-game. Despite a bruising style that results in him getting hacked as much or more than any player not named LeBron, his only missed game since the 14-15 season happened in March of 2015 when he was suspended. He’s led the league in minutes played the past two seasons and appears more than physically capable of doing it again year. Iron Man, Iron Beard? So what, get your minutes Harden.

If you’ve seen OKC during one of its 14-minute stretches each game when Russ sits, then you’ve seen a train wreck of a directionless offense flying off the tracks, careening into the fiery depths of basketball hell. They have just one 5-man lineup that doesn’t include Westbrook and has a positive point differential and that lineup has seen just 4-minutes this season. Westbrook leads the league in both box score plus/minus and VORP (value over replacement player) and his on-off difference is a whopping +25.7. Whether you watch or study the data or just close your eyes and imagine, in any scenario, by any measure, OKC needs Russ like the winter needs the spring.

But if you think a +25.7 on-off is nice, Harden’s with the Rockets is +38.6. Like Westbrook, he appears in Houston’s most productive lineups and has become the singular point of propulsion for this potent offensive attack. Maybe the return of the knee-crushing Beverley does something to reduce Harden’s burden, but he’s never been a traditional point guard/playmaker either, so while his return may assuage some of the wear and tear, it’s not likely to limit the role of the bearded one.

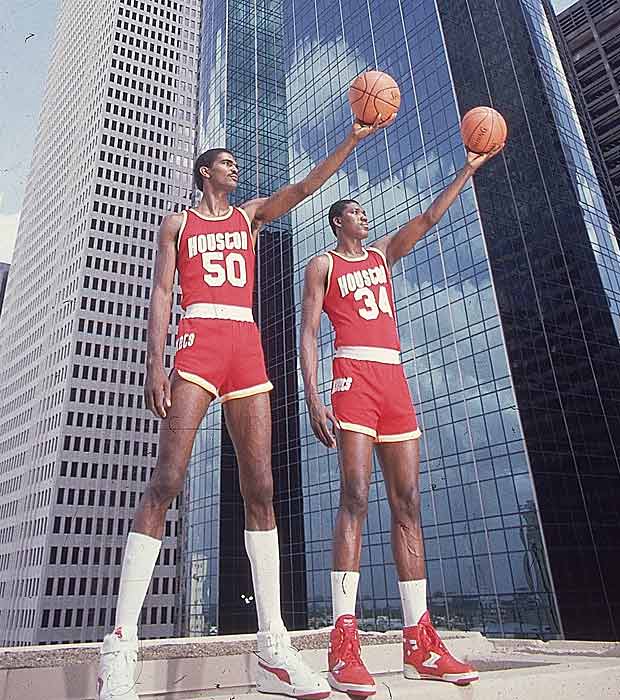

By all visual and statistical appearances, these team’s hopes weigh disproportionately on the shoulders of these native Los Angelinos. It may not meet the aesthetic that some have of basketball, but it does create a space for insanity to reign and for us to plumb the depths of man’s ability to mythologize in a most John Henry (or early MJ) way.

Is it sustainable though? Russ is shooting a career-best 35% from three on a career-high 6 three-point-attempts per-game. Harden is averaging over 40% more than his best assists-per-game average. And both guys are rebounding at career-best levels.

Without Durant, OKC is playing the fastest pace of Westbrook’s career which is resulting in around three more possessions-per-game than at any other time in his career. Harden, conversely, is playing slightly slower than last season, but in line with 14-15. The big flip for Harden is that, per BBR, he’s seeing 98% of his minutes at the point guard position versus 1-2% the previous three seasons. He’s surrounded by glorious shooters like Ryan Anderson, Eric Gordon, Trevor Ariza and even a blossoming Sam Dekker. The variables are in place for both guys to continue churning out offense at gluttonous levels.

Points and assists are so much more in the player’s control than rebounding and while the scoring/assist combinations are the stuff that Oscar Robertson and Nate Archibald can relate to, it’s the rebounding as lead guards that make these players so unique and dangerous. Like LeBron or Magic, both guys can retrieve the defensive board and catch a vulnerable, unset defensive off-balance. As of 11/14, Westbrook leads the league in transition possessions and Harden is tied for 5th. Neither player is exceptionally efficient, which, given the volume of their breaks doesn’t diminish from the overall impact.

All that defensive rebounding-leading-to-breaks aside, Harden maintaining 8-rebounds-per-game or Westbrook at 9 are the most likely stats to fall off.

To put these lines into perspective though, only one player in NBA history has maintained the 30-8-10 line for an entire season. Yep, Mr. Triple-Double himself, Oscar Robertson pulled off the feat three separate seasons: 61-62, 63-64, and 64-65.

Stats courtesy of the great basketball-reference.com – a great website

Like my presumption of Russ and Harden’s toughest counting stat being rebounding, the Big O’s greatest volatility was on the boards where he dropped from 12.5/game as a 23-year-old to a mere 9-10 in subsequent seasons. What makes the Robertson comparison interesting and what makes Russ and Harden’s outputs so damn ridiculous is the difference in pace between the mid-60s and today. Below I’ve included the same table, but with team pace included at the far right:

The numbers are frighteningly similar despite the massive gaps in both minutes played and pace. None of this should take away from the Big O who averaged a triple-double over his first six seasons in the league which spanned 460 games and a 30-10-10 stat line. But it feels almost like Miguel Cabrera winning the Triple Crown a few years back. There are hallowed numbers that feel out of reach, until the savants of today show up with their beards and fringe fashion statements and make you think the impossible is possible. Dinosaurs can walk again – but can they do it for 82 games? Shit man, you’re asking the wrong guy.